Religion

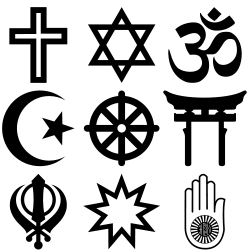

Religion is the belief in and worship of a god or gods, or a set of beliefs concerning the origin and purpose of the universe.[1] It is commonly regarded as consisting of a person’s relation to God or to gods or spirits.[2] Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories associated with their deity or deities, that are intended to give meaning to life. They tend to derive morality, ethics, religious laws or a preferred lifestyle from their ideas about the cosmos and human nature.

The word religion is sometimes used interchangeably with faith or belief system, but it is more than private belief and has a public aspect. Most religions have organised behaviors, congregations for prayer, priestly hierarchies, holy places and scriptures.

The development of religion has taken different forms in different cultures. Some religions place greater emphasis on belief, some on practice. Some emphasise the subjective experience of the religious individual, some the activities of the community. Some religions are said to be universalistic, intending their claims to be binding on everyone, in contrast to ethnic religions, intended only for one group. Religion often makes use of meditation, music and art. In many places it has been associated with public institutions such as education and the family and with government and political power.

One of the more influential theories of religion today is social constructionism, which says that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

| Religions by country |

|---|

|

North America

South America

Europe

Middle East

Asia

Oceania

Religion Portal |

Contents |

Etymology

Religion (from O.Fr. religion "religious community," from L. religionem (nom. religio) "respect for what is sacred, reverence for the gods,"[3] "obligation, the bond between man and the gods"[4]) is derived from the Latin religiō, the ultimate origins of which are obscure. One possibility is derivation from a reduplicated *le-ligare, an interpretation traced to Cicero connecting lego "read", i.e. re (again) + lego in the sense of "choose", "go over again" or "consider carefully". Modern scholars such as Tom Harpur and Joseph Campbell favor the derivation from ligare "bind, connect", probably from a prefixed re-ligare, i.e. re (again) + ligare or "to reconnect," which was made prominent by St. Augustine, following the interpretation of Lactantius.[5][6]

According to the philologist Max Müller, the root of the English word "religion", the Latin religio, was originally used to mean only "reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety" (which Cicero further derived to mean "diligence").[7][8] Max Müller characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called "law".[9]

Many languages have words that can be translated as "religion", but they may use them in a very different way, and some have no word for religion at all. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as "religion", also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of power.[10][11]

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[12] One of its central concepts is "halakha", sometimes translated as "law"", which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.

The use of other terms, such as obedience to God or Islam are likewise grounded in particular histories and vocabularies.[13]

Religious belief

Religious belief usually relates to the existence, nature, and worship of a deity or deities and divine involvement in the universe and human life. Alternately, it may also relate to values and practices transmitted by a spiritual leader.[14] In some religions, like the Abrahamic religions, it is held that most of the core beliefs have been divinely revealed.

Different religions attach differing degrees of importance to belief. Christianity puts more emphasis on belief than other religions. The Church has throughout its history set out Creeds that define correct belief for Christians and identify heresy. Luke Timothy Johnson in his book on the Christian Creed says that "Most religions put more emphasis on orthopraxy (right practice) than on orthodoxy (right belief). Judaism and Islam have each created sophisticated systems of law to guide behaviour, but have allowed an astonishing freedom of conviction and intellectual expression. Both have been able to get along with comparatively short statements of belief. Buddhism and Hinduism concentrate on the practices of ritual and transformation rather than on uniformity of belief, and tribal religions express their view of reality through a variety of myths, not a 'rule of faith' for their members." Christianity by contrast places a peculiar emphasis on belief and has created ever more elaborate and official statements in its Creeds.[15] Some Christian denominations, especially those formed since the Reformation, do not have creeds, and some, for example the Jehovah's Witnesses,[16] explicitly reject them.

Whether Judaism entails belief or not has been a point of some controversy. Some say it is does not,[17] some have suggested that belief is relatively unimportant for Jews. "To be a Jew," says de Lange, "means first and foremost to belong to a group, the Jewish people, and the religious beliefs are secondary."[18] Others say that the the Shema prayer, recited in the morning and evening services, expresses a Jewish creed: "Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One."[Deut. 6:4] Maimonides's Thirteen Principles of the Faith are often taken as the statement of Judaism' fundamental beliefs. They may be summarised as follows:

-

- God is the Creator.

- God is a unity.

- God is incorporeal.

- God is the first and the last.

- It is right to pray to God and to no other.

- The words of the prophets are true.

- The prophecy of Moses was true.

- The Torah was given to Moses.

- The Torah will never change.

- God knows all the deeds of human beings and all their thoughts.

- God rewards those who keep His commandments and punishes those that transgress them.

- The Messiah will come.

- The dead will be resurrected.

Muslims declare the shahada, or testimony: "I bear witness that there is nothing worthy of worship except Allah, and I bear witness that Muhammad is the slave and messenger of Allah."[19]

Religious movements

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the academic practice of comparative religion divided religious belief into philosophically defined categories called "world religions." However, some recent scholarship has argued that not all types of religion are necessarily separated by mutually exclusive philosophies, and furthermore that the utility of ascribing a practice to a certain philosophy, or even calling a given practice religious, rather than cultural, political, or social in nature, is limited.[20][21][22] The current state of psychological study about the nature of religiousness suggests that it is better to refer to religion as a largely invariant phenomenon that should be distinguished from cultural norms (i.e. "religions").[23] The list of religious movements given here is therefore an attempt to summarize the most important regional and philosophical influences on local communities, but it is by no means a complete description of every religious community, nor does it explain the most important elements of individual religiousness.

The four largest religious groups by population, estimated to account for between 5 and 6 billion people, are Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism.

| Four largest religions | Adherents | % of world population | Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| World population | 6.8 billion[24] | Figures taken from individual articles: | |

| Christianity | 1.9 billion – 2.1 billion[25] | 29% – 32% | Christianity by country |

| Islam | 1.3 billion – 1.57 billion[26] | 19% – 21% | Islam by country |

| Buddhism | 500 million – 1.5 billion[27][28] | 7% – 21% | Buddhism by country |

| Hinduism | 950 million – 1 billion[29] | 14% – 20% | Hinduism by country |

| Total | 4.65 billion – 6.17 billion | 68.38% – 90.73% | |

- Abrahamic religions are monotheistic religions which believe they descend from the Jewish patriarch Abraham.

-

- Judaism is the oldest Abrahamic religion, originating in the people of ancient Israel and Judea. Judaism is based primarily on the Torah, a text which Jews believe was handed down to the people of Israel through the prophet Moses in 1,400 BCE. This along with the rest of the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud are the central texts of Judaism. The Jewish people were scattered after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. Judaism today is practiced by about 13 million people, with about 40 per cent living in Israel and 40 per cent in the United States.

- Christianity is based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (1st century) as presented in the New Testament. The Christian faith is essentially faith in Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God, and as Savior and Lord. Almost all Christians believe in the Trinity, which teaches the unity of Father, Son (Jesus Christ), and Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead. Most Christians can describe their faith with the Nicene Creed. As the religion of Byzantine Empire in the first millennium and of Western Europe during the time of colonization, Christianity has been propagated throughout the world. The main divisions of Christianity are, according to the number of adherents:

- Catholic Church, leaded by the Pope in Rome, is a communion of the Western church and 22 Eastern Catholic churches.

- Protestantism, separated from the Catholic Church in the 16th-century Reformation and split in many denominations,

- Eastern Christianity which include Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and the Church of the East.

-

- Islam refers to the religion taught by the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a major political and religious figure of the 7th century CE. Islam is the dominant religion of northern Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. As with Christianity, there is no single orthodoxy in Islam but a multitude of traditions which are generally categorized as Sunni and Shia, although there are other minor groups as well. Wahhabi is the dominant Muslim sect in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. There are also several Islamic republics, including Iran, which is run by a Shia Supreme Leader.

- The Bahá'í Faith was founded in the 19th century in Iran and since then has spread worldwide. It teaches unity of all religious philosophies and accepts all of the prophets of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as well as additional prophets including its founder Bahá'u'lláh.

- American religions are often derived from Christian tradition. They include the Latter Day Saint movement, Jehovah's Witnesses among hundreds of smaller groups.

- Smaller Abrahamic groups that are not heterodox versions of the four major groupings include Samaritanism, the Druze, and the Rastafari movement.

- Indian religions are practiced or were founded in the Indian subcontinent. Concepts most of them share in common include dharma, karma, reincarnation, mantras, yantras, and darśana.

- Hinduism is a synecdoche describing the similar philosophies of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and related groups practiced or were founded in the Indian subcontinent. Concepts most of them share in common include karma, caste, reincarnation, mantras, yantras, and darśana.[30] Hinduism is not a monolithic religion in the Romanic sense but a religious category containing dozens of separate philosophies amalgamated as Sanātana Dharma.

- Jainism, taught primarily by Parsva (9th century BCE) and Mahavira (6th century BCE), is an ancient Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence for all forms of living beings in this world. Jains are found mostly in India.

- Buddhism was founded by Siddhattha Gotama in the 6th century BCE. Buddhists generally agree that Gotama aimed to help sentient beings end their suffering by understanding the true nature of phenomena, thereby escaping the cycle of suffering and rebirth (saṃsāra), that is, achieving Nirvana.

- Theravada Buddhism, which is practiced mainly in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia alongside folk religion, shares some characteristics of Indian religions. It is based in a large collection of texts called the Pali Canon.

- Under the heading of Mahayana (the "Great Vehicle") fall a multitude of doctrines which began their development in China and are still relevant in Vietnam, in Korea, in Japan, and to a lesser extent in Europe and the United States. Mahayana Buddhism includes such disparate teachings as Zen, Pure Land, and Soka Gakkai.

- Vajrayana Buddhism, sometimes considered a form of Mahayana, was developed in Tibet and is still most prominent there and in surrounding regions.

- Two notable new Buddhist sects are Hòa Hảo and the Dalit Buddhist movement, which were developed separately in the 20th century.

- Sikhism is a monotheistic religion founded on the teachings of Guru Nanak and ten successive Sikh Gurus in 15th century Punjab. Sikhs are found mostly in India.

- There are dozens of new religious movements within Indian religions and Hindu reform movements, such as Ayyavazhi and Swaminarayan Faith.

- Iranian religions are ancient religions which roots predate the Islamization of the Greater Iran. Nowadays these religions are practiced only by minorities.

- Zoroastrianism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster in the 6th century BC. The Zoroastrians worship the Creator Ahura Mazda. In Zoroastrianism good and evil have distinct sources, with evil trying to destroy the creation of Mazda, and good trying to sustain it.

- Mandaeism is a monotheistic religion with a strongly dualistic worldview. Mandaeans are sometime labeled as the "Last Gnostics".

- Kurdish religions include the traditional beliefs of the Yazidi, Alevi, and Ahl-e Haqq. Sometimes these are labeled Yazdânism.

- Folk religion is a term applied loosely and vaguely to less-organized local practices. It is also called paganism, shamanism, animism, ancestor worship, and totemism, although not all of these elements are necessarily present in local belief systems. The category of "folk religion" can generally include anything that is not part of an organization. The modern neopagan movement draws on folk religion for inspiration.

- African traditional religion is a category including any type of religion practiced in Africa before the arrival of Islam and Christianity, such as Yoruba religion or San religion. There are many varieties of religions developed by Africans in the Americas derived from African beliefs, including Santería, Candomblé, Umbanda, Vodou, and Oyotunji.

- Folk religions of the Americas include Aztec religion, Inca religion, Maya religion, and modern Catholic beliefs such as the Virgin of Guadalupe. Native American religion is practiced across the continent of North America.

- Australian Aboriginal culture contains a mythology and sacred practices characteristic of folk religion.

- Chinese folk religion, practiced by Chinese people around the world, is a primarily social practice including popular elements of Confucianism and Taoism, with some remnants of Mahayana Buddhism. Most Chinese do not identify as religious due to the strong Maoist influence on the country in recent history, but adherence to religious ceremonies remains common. New religious movements include Falun Gong and I-Kuan Tao.

- Traditional Korean religion was a syncretic mixture of Mahayana Buddhism and Korean shamanism. Unlike Japanese Shinto, Korean shamanism was never codified and Buddhism was never made a social necessity. In some areas these traditions remain prevalent, but Korean-influenced Christianity is far more influential in society and politics.

- Traditional Japanese religion is a mixture of Mahayana Buddhism and ancient indigenous practices which were codified as Shinto in the 19th century. Japanese people retain nominal attachment to both Buddhism and Shinto through social ceremonies, but irreligion is common.

- A variety of new religious movements still practiced today have been founded in many other countries besides Japan and the United States, including:

- Shinshūkyō is a general category for a wide variety of religious movements founded in Japan since the 19th century. These movements share almost nothing in common except the place of their founding. The largest religious movements centered in Japan include Soka Gakkai, Tenrikyo, and Seicho-No-Ie among hundreds of smaller groups.

- Cao Đài is a syncretistic, monotheistic religion, established in Vietnam in 1926.

- Unitarian Universalism is a religion characterized by support for a "free and responsible search for truth and meaning."

Sociological classifications of religious movements suggest that within any given religious group, a community can resemble various types of structures, including "churches", "denominations", "sects", "cults", and "institutions".

Mysticism and esotericism

Mysticism focuses on methods other than logic, but (in the case of esoteric mysticism) not necessarily excluding it, for gaining enlightenment. Rather, meditative and contemplative practices such as Vipassanā and yoga, physical disciplines such as stringent fasting and whirling (in the case of the Sufi dervishes), or the use of psychoactive drugs such as LSD, lead to altered states of consciousness that logic can never hope to grasp. However, regarding the latter topic, mysticism prevalent in the 'great' religions (monotheisms, henotheisms, which are perhaps relatively recent, and which the word 'mysticism' is more recent than,) includes systems of discipline that forbid drugs that can damage the body, including the nervous system.

Mysticism (to initiate) is the pursuit of communion with, or conscious awareness of ultimate reality, the divine, spiritual truth, or Deity through direct, personal experience (intuition or insight) rather than rational thought. Mystics speak of the existence of realities behind external perception or intellectual apprehension that are central to being and directly accessible through personal experience. They say that such experience is a genuine and important source of knowledge.

Esotericism is often spiritual (thus religious) but can be non-religious/-spiritual, and it uses intellectual understanding and reasoning, intuition and inspiration (higher noetic and spiritual reasoning,) but not necessarily faith (except often as a virtue,) and it is philosophical in its emphasis on techniques of psycho-spiritual transformation (esoteric cosmology). Esotericism refers to "hidden" knowledge available only to the advanced, privileged, or initiated, as opposed to exoteric knowledge, which is public. All religions are probably somewhat exoteric, but most ones of ancient civilizations such as Yoga of India, and the mystery religions of ancient Egypt, Israel (Kabbalah), and Greece are examples of ones that are also esoteric.

Spirituality

Members of an organized religion may not see any significant difference between religion and spirituality. Or they may see a distinction between the mundane, earthly aspects of their religion and its spiritual dimension.

Some individuals draw a strong distinction between religion and spirituality. They may see spirituality as a belief in ideas of religious significance (such as God, the Soul, or Heaven), but not feel bound to the bureaucratic structure and creeds of a particular organized religion. They choose the term spirituality rather than religion to describe their form of belief, perhaps reflecting a disillusionment with organized religion (see Major religious groups), and a movement towards a more "modern" — more tolerant, and more intuitive — form of religion. These individuals may reject organized religion because of historical acts by religious organizations, such as Christian Crusades and Islamic Jihad, the marginalisation and persecution of various minorities or the Spanish Inquisition. The basic precept of the ancient spiritual tradition of India, the Vedas, is the inner reality of existence, which is essentially a spiritual approach to being.

Types of religion

| Religious history founding figures |

|

Origins |

| Prehistoric

Ancient Near East |

|

Abrahamic |

Some scholars classify religions as either universal religions that seek worldwide acceptance and actively look for new converts, or ethnic religions that are identified with a particular ethnic group and do not seek converts.[33] Others reject the distinction, pointing out that all religious practices, whatever their philosophical origin, are ethnic because they come from a particular culture.[34][35][36]

Modern issues in religion

Interfaith cooperation

Because religion continues to be recognized in Western thought as a universal impulse, many religious practitioners have aimed to band together in interfaith dialogue and cooperation. The first major dialogue was the Parliament of the World's Religions at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, which remains notable even today both in affirming "universal values" and recognition of the diversity of practices among different cultures. The 20th century has been especially fruitful in use of interfaith dialogue as a means of solving ethnic, political, or even religious conflict, with Christian-Jewish reconciliation representing a complete reverse in the attitudes of many Christian communities towards Jews.

Secularism and irreligion

As religion became a more personal matter in western culture, discussions of society found a new focus on political and scientific meaning, and religious attitudes (dominantly Christian) were increasingly seen as irrelevant for the needs of the European world. On the political side, Ludwig Feuerbach recast Christian beliefs in light of humanism, paving the way for Karl Marx's famous characterization of religion as "the opium of the people". Meanwhile, in the scientific community, T.H. Huxley in 1869 coined the term "agnostic," a term—subsequently adopted by such figures as Robert Ingersoll—that, while directly conflicting with and novel to Christian tradition, is accepted and even embraced in some other religions. Later, Bertrand Russell told the world Why I Am Not a Christian, which influenced several later authors to discuss their breakaway from their own religious uprbringings from Islam to Hinduism.

The terms "atheist" (lack of belief in any gods) and "agnostic" (belief in the unknowability of the existence of gods), though specifically contrary to theistic (e.g. Christian, Jewish, and Muslim) religious teachings, do not by definition mean the opposite of "religious". There are religions (including Buddhism and Taoism), in fact, that classify some of their followers as agnostic, atheistic, or nontheistic.

The true opposite of "religious" is the word "irreligious". Irreligion describes an absence of any religion; antireligion describes an active opposition or aversion toward religions in general.

Critics of religious systems as well as of personal faith have posed a variety of arguments against religion. Some modern-day critics hold that religion lacks utility in human society; they may regard religion as irrational.[37] Some assert that dogmatic religions are morally deficient, elevating as they do to moral status ancient, arbitrary, and ill-informed rules.[38]

Related forms of thought

Religion and philosophy

Religion and philosophy meet in several areas — notably in the study of metaphysics and cosmology. In particular, a distinct set of religious beliefs will often entail a specific metaphysics and cosmology. That is, a religion will generally offer answers to metaphysical and cosmological questions about the nature of being, of the universe, humanity, and the divine.

Religion and superstition

Superstition may be said to be belief in non-causal links between unconnected things. Religions is more complex and includes social institutions and morality. But religions may include superstitions or make use of magical thinking. Members of one religion often think other religions as superstitious.[39][40] Some atheists, agnostics, deists, and skeptics regard religious belief as superstition. Religious practices are likely to be labeled "superstitious" when they include belief in miracles or extraordinary events, supernatural interventions, apparitions, charms, omens, incantations, an afterlife or the efficacy of prayer..

Greek and Roman pagans, who saw their relations with the gods in political and social terms, scorned the man who constantly trembled with fear at the thought of the gods (deisidaimonia), as a slave might fear a cruel and capricious master. The Romans called such fear of the gods superstitio.[41] Early Christianity was outlawed as a superstitio Iudaica, a "Jewish superstition", by Domitian in the 80s AD. In AD 425, when Rome had become Christian, Theodosius II outlawed pagan traditions as superstitious.

The Roman Catholic Church considers superstition to be sinful in the sense that it denotes a lack of trust in the divine providence of God and, as such, is a violation of the first of the Ten Commandments. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that superstition "in some sense represents a perverse excess of religion" (para. #2110). "Superstition," it says, "is a deviation of religious feeling and of the practices this feeling imposes. It can even affect the worship we offer the true God, e.g., when one attributes an importance in some way magical to certain practices otherwise lawful or necessary. To attribute the efficacy of prayers or of sacramental signs to their mere external performance, apart from the interior dispositions that they demand is to fall into superstition. Cf. Matthew 23:16-22" (para. #2111)

Myth

The word myth has several meanings.

- A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

- A person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence; or

- A metaphor for the spiritual potentiality in the human being.[42]

Ancient polytheistic religions, such as those of Greece, Rome, and Scandinavia, are usually categorized under the heading of mythology. Religions of pre-industrial peoples, or cultures in development, are similarly called "myths" in the anthropology of religion. The term "myth" can be used pejoratively by both religious and non-religious people. By defining another person's religious stories and beliefs as mythology, one implies that they are less real or true than one's own religious stories and beliefs. Joseph Campbell remarked, "Mythology is often thought of as other people's religions, and religion can be defined as mis-interpreted mythology."[43]

In sociology, however, the term myth has a non-pejorative meaning. There, myth is defined as a story that is important for the group whether or not it is objectively or provably true. Examples include the death and resurrection of Jesus, which, to Christians, explains the means by which they are freed from sin and is also ostensibly a historical event. But from a mythological outlook, whether or not the event actually occurred is unimportant. Instead, the symbolism of the death of an old "life" and the start of a new "life" is what is most significant. Religious believers may or may not accept such symbolic interpretations.

Religion and the law

There are laws and statutes that make reference to religion.[44] This has led to claims from some scholars that religious freedom is literally impossible to uphold.[45] Also, the Western legal principle of separation of church and state tends to engender a new, more inclusive civil religion.[46]

Religion and science

Religious knowledge, according to religious practitioners, may be gained from religious leaders, sacred texts (scriptures), and/or personal revelation. Some religions view such knowledge as unlimited in scope and suitable to answer any question; others see religious knowledge as playing a more restricted role, often as a complement to knowledge gained through physical observation. Some religious people maintain that religious knowledge obtained in this way is absolute and infallible (religious cosmology).

The scientific method gains knowledge by testing hypotheses to develop theories through elucidation of facts or evaluation by experiments and thus only answers cosmological questions about the physical universe. It develops theories of the world which best fit physically observed evidence. All scientific knowledge is subject to later refinement in the face of additional evidence. Scientific theories that have an overwhelming preponderance of favorable evidence are often treated as facts (such as the theories of gravity or evolution).

Many scientists have held strong religious beliefs (see List of Christian thinkers in science and List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics) and have worked to harmonize science and religion. Isaac Newton, for example, believed that gravity caused the planets to revolve about the Sun, and credited God with the design. In the concluding General Scholium to the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, he wrote: "This most beautiful System of the Sun, Planets and Comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful being." Nevertheless, conflict has repeatedly arisen between religious organizations and individuals who propagated scientific theories that were deemed unacceptable by the organizations. The Roman Catholic Church, for example, has in the past[47] reserved to itself the right to decide which scientific theories were acceptable and which were unacceptable. In the 17th century, Galileo was tried and forced to recant the heliocentric theory based on the church's stance that the Greek Hellenistic system of astronomy was the correct one.[48][49]

Today, religious belief among scientists is less prevalent than it is in the general public. Surveys on the subject give varying results. The Pew Research Center found in 2009 that 33% of American scientists and 83% of the general public believe in God, another 18% of scientists and 12% of the public believe more generally in a higher power, and 41% of scientists and 4% of the public believe in neither.[50] A mailed survey to members of the National Academy of Sciences found that 7% of respondents to believed in a personal God.[51] Elaine Howard Ecklund found that about two-thirds of scientists at elite research universities believed in God[52] and that nearly 50 percent of them were religious.[53][54]

The philosophical theory of pragmatism (first propounded by William James) has been used to reconcile scientific with religious knowledge. Pragmatism holds that the truth of a set of beliefs is indicated by its usefulness in helping people cope with a particular context of life. Thus, the fact that scientific beliefs are useful in predicting observations in the physical world can indicate a certain truth for scientific theories and the fact that religious beliefs can be useful in helping people cope with difficult emotions or moral decisions can indicate a certain truth for those beliefs. (For a similar postmodern view, see grand narrative.)

The Catholic Church has always concurred with Augustine of Hippo who explicitly opposed a literal interpretation of the Bible whenever the Bible conflicted with science. The literal way to read the sacred texts became especially prevalent after the rise of the Protestant reformation, with its emphasis on the Bible as the only authoritative source concerning the ultimate reality.[55] This view is often shunned by both religious leaders (who regard literally believing it as petty and look for greater meaning instead) and scientists who regard it as an impossibility.

Some Christians have disagreed with the validity of Keplerian astronomy, the theory of evolution, the scientific account of the creation of the universe and the origins of life. However, Stanley Jaki has suggested that the Christian worldview was a crucial in the emergence of modern science. Historians are moving away from the view that Christianity was always in conflict with science—the so-called conflict thesis.[56][57] Gary Ferngren in his historical volume about science and religion states: "While some historians had always regarded the conflict thesis as oversimplifying and distorting a complex relationship, in the late 20th century it underwent a more systematic reevaluation. The result is the growing recognition among historians of science that the relationship of religion and science has been much more positive than is sometimes thought. Although popular images of controversy continue to exemplify the supposed hostility of Christianity to new scientific theories, studies have shown that Christianity has often nurtured and encouraged scientific endeavour, while at other times the two have co-existed without either tension or attempts at harmonization. If Galileo and the Scopes trial come to mind as examples of conflict, they were the exceptions rather than the rule."[58]

In the Bahá'í Faith, the harmony of science and religion is a central tenet.[59] The principle states that that truth is one, and therefore true science and true religion must be in harmony, thus rejecting the view that science and religion are in conflict.[59] `Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of the founder of the religion, asserted that science and religion cannot be opposed because they are aspects of the same truth; he also affirmed that reasoning powers are required to understand the truths of religion and that religious teachings which are at variance with science should not be accepted; he explained that religion has to be reasonable since God endowed humankind with reason so that they can discover truth.[60] Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, described science and religion as "the two most potent forces in human life."[61]

Proponents of Hinduism claim that it is not afraid of scientific explorations, nor of the technological progress of mankind. According to them, there is a comprehensive scope and opportunity for Hinduism to mold itself according to the demands and aspirations of the modern world; it has the ability to align itself with both science and spiritualism. This religion uses some modern examples to explain its ancient theories and reinforce its own beliefs. For example, some Hindu thinkers have used the terminology of quantum physics to explain some basic concepts of Hinduism such as Maya or the illusory and impermanent nature of our existence.

Evolutionary theory and religion

At one time, evolutionists explained religion as something that conferred a biological advantages to its adherents. More recently, Richard Dawkins has explained it in terms of the evolution of self-replicating ideas, or memes as he calls them, distinct from any resulting biological advantages they might bestow.[62] Susan Blackmore regards religions as particularly tenacious memes.[63] Chris Hedges regards meme theory as a misleading imposition of genetics onto psychology.

Religion as a Christian concept

The social constructionists

In recent years, some academic writers have described religion according to the theory of social constructionism, which considers how ideas and social phenomena develop in a social context. Among the main proponents of this theory of religion are Timothy Fitzgerald, Daniel Dubuisson and Talad Assad. The social constructionists argue that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

Dubuisson, a French anthropologist, says that the idea of religion has changed a lot over time and that one cannot fully understand its development by relying on etymology, which "tends to minimize or cancel out the role of history".[64] "What the West and the history of religions in its wake have objectified under the name 'religion'", he says, " is ... something quite unique, which could be appropriate only to itself and its own history."[64] He notes that St. Augustine's definition of religio differed from the way we used the modern word "religion".[64] Dubuisson prefers the term "cosmographic formation" to religion. Dubuisson says that, with the emergence of religion as a category separate from culture and society, there arose religious studies. The initial purpose of religious studies was to demonstrate the superiority of the "living" or "universal" European world view to the "dead" or "ethnic" religions scattered throughout the rest of the world, expanding the teleological project of Schleiermacher and Tiele to a worldwide ideal religiousness.[65] Due to shifting theological currents, this was eventually supplanted by a liberal-ecumenical interest in searching for Western-style universal truths in every cultural tradition.[66] Clifford Geertz's definition of religion as a "cultural system" was dominant for most of the 20th century and continues to be widely accepted today.

According to Fitzgerald, the history of other cultures' interaction with the religious category is not about a universal constant, but rather concerns a particular idea that first developed in Europe under the influence of Christianity.[67] Fitzgerald argues that from about the 4th century CE Western Europe and the rest of the world diverged. As Christianity became commonplace, the charismatic authority identified by Augustine, a quality we might today call "religiousness", exerted a commanding influence at the local level. This system persisted in the eastern Byzantine Empire following the East-West Schism, but Western Europe regulated unpredictable expressions of charisma through the Roman Catholic Church. As the Church lost its dominance during the Protestant Reformation and Christianity became closely tied to political structures, religion was recast as the basis of national sovereignty, and religious identity gradually became a less universal sense of spirituality and more divisive, locally defined, and tied to nationality.[68] It was at this point that "religion" was dissociated with universal beliefs and moved closer to dogma in both meaning and practice. However there was not yet the idea of dogma as personal choice, only of established churches. With the Enlightenment religion lost its attachment to nationality, says Fitzgerald, but rather than becoming a universal social attitude, it now became a personal feeling or emotion.[69] Friedrich Schleiermacher in the late 18th century defined religion as das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl, commonly translated as "a feeling of absolute dependence".[70] His contemporary Hegel disagreed thoroughly, defining religion as "the Divine Spirit becoming conscious of Himself through the finite spirit."[71] William James is an especially notable 19th century subscriber to the theory of religion as feeling.

Asad argues that before the word "religion" came into common usage, Christianity was a disciplina, a "rule" just like that of the Roman Empire. This idea can be found in the writings of St. Augustine (354–430). Christianity was then a power structure opposing and superseding human institutions, a literal Kingdom of Heaven. It was the discipline taught by one's family, school, church, and city authorities, rather than something calling one to self-discipline through symbols.[72]

These ideas are developed by N. Balagangadhara. In the Age of Enlightenment, Balagangadhara says that the idea of Christianity as the purest expression of spirituality was supplanted by the concept of "religion" as a worldwide practice.[73] This caused such ideas as religious freedom, a reexamination of classical philosophy as an alternative to Christian thought, and more radically Deism among intellectuals such as Voltaire. Much like Christianity, the idea of "religious freedom" was exported around the world as a civilizing technique, even to regions such as India that had never treated spirituality as a matter of political identity.[20] In Japan, where Buddhism was still seen as a philosophy of natural law,[74] the concept of "religion" and "religious freedom" as separate from other power structures was unnecessary until Christian missionaries demanded free access to conversion, and when Japanese Christians refused to engage in patriotic events.[75]

Other writers

Similar views have been put forward by writers who are not social constructionists. George Lindbeck, a Lutheran and a postliberal theologian, says that religion does not refer to belief in "God" or a transcendent Absolute, but rather to "a kind of cultural and/or linguistic framework or medium that shapes the entirety of life and thought ... it is similar to an idiom that makes possible the description of realities, the formulation of beliefs, and the experiencing of inner attitudes, feelings, and sentiments.”[76] Nicholas de Lange, Professor of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at Cambridge University, says that "The comparative study of religions is an academic discipline which has been developed within Christian theology faculties, and it has a tendency to force widely differing phenomena into a kind of strait-jacket cut to a Christian pattern. The problem is not only that other 'religions' may have little or nothing to say about questions which are of burning importance for Christianity, but that they may not even see themselves as religions in precisely the same way in which Christianity sees itself as a religion."[77]

See also

- Economics of religion

- Philosophy of religion

- Sociology of religion

- Life stance

- Faith

- Belief

- List of religious populations

- List of religious texts

- Prayer

- Priest

- Religions by country

- Wealth and religion

- Religion and happiness

- Religious conversion

- Nontheistic religions

- Temple

- Theocracy

References

Notes

- ↑ "religion". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/religion.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Brittanica

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "religion". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=religion.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ In The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light. Toronto. Thomas Allen, 2004. ISBN 0-88762-145-7

- ↑ In The Power of Myth, with Bill Moyers, ed. Betty Sue Flowers, New York, Anchor Books, 1991. ISBN 0-385-41886-8

- ↑ Max Müller, Natural Religion, p.33, 1889

- ↑ Lewis & Short, A Latin Dictionary

- ↑ Max Müller. Introduction to the science of religion. p. 28.

- ↑ Toshio Kuroda, Jacqueline I. Stone (translator). "The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23.3-4 (1996)

- ↑ Neil McMullin. Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.

- ↑ Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary, p.3, citing Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? ( Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).

- ↑ Colin Turner. Islam without Allah? New York: Routledge, 2000. pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought, Pascal Boyer, Basic Books (2001)

- ↑ Luke Timothy Johnson, The Creed: What Christians Believe and Why it Matters, Doubleday, 2003

- ↑ "Creeds — Any Place in True Worship?", Awake!, October 8, 1985

- ↑ Menachem Kellner, Must a Jew Believe Anything?, Littman Library of Jewish Civilisation

- ↑ Nicholas de Lange, Judaism, Oxford University Press, 1986.

- ↑ "Proclaiming the Shahada is the First Step Into Islam." Islamic Learning Materials. Accessed: 17 May 2009

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Brian Kemble Pennington Was Hinduism Invented? New York: Oxford University Press US, 2005. ISBN 0195166558

- ↑ Russell T. McCutcheon. Critics Not Caretakers: Redescribing the Public Study of Religion. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.

- ↑ Nicholas Lash. The beginning and the end of 'religion'. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521566355

- ↑ Joseph Bulbulia. "Are There Any Religions? An Evolutionary Explanation." Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 17.2 (2005), pp.71-100

- ↑ [1][2]

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ [6]

- ↑ [7]

- ↑ Hinduism is variously defined as a "religion", "set of religious beliefs and practices", "religious tradition" etc. For a discussion on the topic, see: "Establishing the boundaries" in Gavin Flood (2003), pp. 1-17. René Guénon in his Introduction to the Study of the Hindu Doctrines (1921 ed.), Sophia Perennis, ISBN 0-900588-74-8, proposes a definition of the term "religion" and a discussion of its relevance (or lack of) to Hindu doctrines (part II, chapter 4, p. 58).

- ↑ India – Caste. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Jeffrey Brodd (2003). World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery. Saint Mary's Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780884897255. http://books.google.com/?id=vOzNo4MVlgMC&pg=PA45&dq=%22330+million%22: '[..] many gods and goddesses (traditionally 330 million!) [...] Hinduism generally regards its 330 million as deities as extensions of one ultimate reality, many names for one ocean, many "masks" for one God.'

- ↑ Hinnells, John R. (2005). The Routledge companion to the study of religion. Routledge. pp. 439–440. ISBN 0415333113. http://books.google.com/?id=IGspjXKxIf8C. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ↑ Timothy Fitzgerald. The Ideology of Religious Studies. New York: Oxford University Press USA, 2000.

- ↑ Craig R. Prentiss. Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity. New York: NYU Press, 2003. ISBN 081476701X

- ↑ Tomoko Masuzawa. The Invention of World Religions, or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 0226509885

- ↑ Bryan Caplan. "Why Religious Beliefs Are Irrational, and Why Economists Should Care". http://www.gmu.edu/departments/economics/bcaplan/ldebate.htm. The article about religion and irrationality.

- ↑ Nobel Peace Laureate, Muslim and human rights activist Dr Shirin Ebadi has spoken out against undemocratic Islamic countries justifying "oppressive acts" in the name of Islam. Speaking at the Earth Dialogues 2006 conference in Brisbane, Dr Ebadi pronounced her native Iran - as well as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Yemen "among others" - guilty of violating human rights. "In these countries, Islamic rulers want to solve 21st century issues with laws belonging to 14 centuries ago," she said. "Their views of human rights are exactly the same as it was 1400 years ago."

- ↑ Boyer (2001). "Why Belief". Religion Explained. http://books.google.com/books?id=wreF80OHTicC&pg=PA297&lpg=PA297&dq=%22fang+too+were+quite+amazed%22&source=web&ots=NxCB1FWq5v&sig=SuHHSm8zvnJd8_I2cKp5Zc090R0&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result.

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2007, p. 232

- ↑ Veyne 1987, p 211 )

- ↑ Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, p. 22 ISBN 0-385-24774-5

- ↑ Joseph Campbell, Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor. Ed. Eugene Kennedy. New World Library ISBN 1-57731-202-3.

- ↑ An example is the Establishment Clause in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. However the US Supreme Court has intentionally not pinned down a precise legal definition to allow for flexibility in preserving rights for what might be regarded as a religion over time. [8]

- ↑ Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, The Impossibility of Religious Freedom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- ↑ Ronald C. Wimberley and James A. Christenson. "Civil Religion and Church and State". The Sociological Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Winter, 1980), pp. 35-40

- ↑ Quotation: "The Second Vatican Council affirmed academic freedom for natural science and other secular disciplines". From the essay of Ted Peters about Science and Religion at "Lindsay Jones (editor in chief). Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition. Thomson Gale. 2005. p.8185"

- ↑ By Dr Paul Murdin, Lesley Murdin Photographs by Paul New. Supernovae Astronomy Murdin Published 1985, Cambridge UniversityPress Science,256 pages,ISBN 052130038X page 18.

- ↑ Godfrey-Smith, Peter. 2003. Theory and reality: an introduction to the philosophy of science. Science and its conceptual foundations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Page 14.

- ↑ Pew Research Center: "Public Praises Science; Scientists Fault Public, Media", Section 4: Scientists, Politics and Religion. July 9, 2009.

- ↑ Edward J. Larson and Larry Witham, Leading scientists still reject God, in Nature July 23, 1998

- ↑ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/8916982/

- ↑ http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/ReligionTheology/SociologyofReligion/?view=usa&ci=9780195392982

- ↑ Elaine Howard Ecklund (2010). Science Vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 9780195392982. http://books.google.com/books?id=v6Pn1kbYjAEC. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Stanley Jaki. Bible and Science, Christendom Press, 1996 (pages 110-111)

- ↑ Spitz, Lewis (1987). (The Rise of modern Europe) The protestant Reformation 1517-1559.. Harper Torchbooks. pp. 383. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/0-06-132069-2 For example, Lewis Spitz says "To set up a 'warfare of science and theology' is an exercise in futility and a reflection of a nineteenth century materialism now happily transcended"|0-06-132069-2 For example, Lewis Spitz says "To set up a 'warfare of science and theology' is an exercise in futility and a reflection of a nineteenth century materialism now happily transcended"]].

- ↑ Quotation: "The conflict thesis, at least in its simple form, is now widely perceived as a wholly inadequate intellectual framework within which to construct a sensible and realistic historiography of Western science." (p. 7), from the essay by Colin A. Russell "The Conflict Thesis" on "Gary Ferngren (editor). Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0".

- ↑ Gary Ferngren (editor). Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0. (Introduction, p. ix)

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Esslemont, J.E. (1980). Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era (5th ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-160-4.

- ↑ `Abdu'l-Bahá (1982) [1912]. The Promulgation of Universal Peace (Hardcover ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-172-8. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/ab/PUP/.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1938). The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-231-7. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/WOB/index.html.

- ↑ Dawkins 1989, p. 352

- ↑ Blackmore 1999

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Daniel Dubuisson, The Western Construction of Religion

- ↑ Daniel Dubuisson. "Exporting the Local: Recent Perspectives on 'Religion' as a Cultural Category", Religion Compass, 1.6 (2007), p.792.

- ↑ Tomoko Masuzawa, The Invention of World Religions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Timothy (2007). Discourse on Civility and Barbarity. Oxford University Press. pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2007, p. 194

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2007, p. 268

- ↑ Hueston A. Finlay. "‘Feeling of absolute dependence’ or ‘absolute feeling of dependence’? A question revisited". Religious Studies 41.1 (2005), pp.81-94.

- ↑ Max Müller. "Lectures on the origin and growth of religion."

- ↑ Talal Asad, Genealogies of Religion. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1993 p.34-35.

- ↑ S. N. Balagangadhara. The Heathen in His Blindness... New York: Brill Academic Publishers, 1994. p.159.

- ↑ Jason Ānanda Josephson. "When Buddhism Became a 'Religion'". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33.1: 143–168.

- ↑ Isomae Jun’ichi. "Deconstructing 'Japanese Religion'". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32.2: 235–248.

- ↑ George A. Lindbeck, Nature of Doctrine (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1984), 33.

- ↑ Nicholas de Lange, Judaism, Oxford University Press, 1986

Bibliography

- Saint Augustine; The Confessions of Saint Augustine (John K. Ryan translator); Image (1960), ISBN 0-385-02955-1.

- Descartes, René; Meditations on First Philosophy; Bobbs-Merril (1960), ISBN 0-672-60191-5.

- Barzilai, Gad; Law and Religion; The International Library of Essays in Law and Society; Ashgate (2007),ISBN 978-0-7546-2494-3

- Durant, Will (& Ariel (uncredited)); Our Oriental Heritage; MJF Books (1997), ISBN 1-56731-012-5.

- Durant, Will (& Ariel (uncredited)); Caesar and Christ; MJF Books (1994), ISBN 1-56731-014-1

- Durant, Will (& Ariel (uncredited)); The Age of Faith; Simon & Schuster (1980), ISBN 0-671-01200-2.

- Marija Gimbutas 1989. The Language of the Goddess. Thames and Hudson New York

- Gonick, Larry; The Cartoon History of the Universe; Doubleday, vol. 1 (1978) ISBN 0-385-26520-4, vol. II (1994) ISBN#0-385-42093-5, W. W. Norton, vol. III (2002) ISBN 0-393-05184-6.

- Haisch, Bernard The God Theory: Universes, Zero-point Fields, and What's Behind It All -- discussion of science vs. religion (Preface), Red Wheel/Weiser, 2006, ISBN 1-57863-374-5

- Lao Tzu; Tao Te Ching (Victor H. Mair translator); Bantam (1998).

- Marx, Karl; "Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right", Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, (1844).

- Saler, Benson; "Conceptualizing Religion: Immanent Anthropologists, Transcendent Natives, and Unbounded Categories" (1990), ISBN 1-57181-219-9

- The Holy Bible, King James Version; New American Library (1974).

- The Koran; Penguin (2000), ISBN 0-14-044558-7.

- The Origin of Live & Death, African Creation Myths; Heinemann (1966).

- Poems of Heaven and Hell from Ancient Mesopotamia; Penguin (1971).

- The World Almanac (annual), World Almanac Books, ISBN 0-88687-964-7.

- The Serotonin System and Spiritual Experiences - American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1965-1969, November 2003.

- United States Constitution

- Selected Work Marcus Tullius Cicero

- The World Almanac (for numbers of adherents of various religions), 2005

- Religion [First Edition]. Winston King. Encyclopedia of Religion. Ed. Lindsay Jones. Vol. 11. 2nd ed. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. p7692-7701.

- World Religions and Social Evolution of the Old World Oikumene Civilizations: A Cross-cultural Perspective by Andrey Korotayev, Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004, ISBN 0-7734-6310-0.

- Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

On religion definition:

- The first major study: Durkheim, Emile (1976) The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: George Allen & Unwin (in French 1912, English translation 1915).

- Wilfred Cantwell Smith The Meaning and End of Religion (1962) notes that the concept of religion as an ideological community and system of doctrines, developed in the 15th and 16th centuries CE.

- A distillation of the Western folk category of religion: Geertz, Clifford. 1993 [1966]. Religion as a cultural system. pp. 87–125 in Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. London: Fontana Press.

- An operational definition: Wallace, Anthony F. C. 1966. Religion: An Anthropological View. New York: Random House. (p. 62-66)

- A recent overview: A Scientific Definition of Religion. By Ph.D. James W. Dow.

Studies of religion in particular geographical areas:

- A. Khanbaghi. The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran (IB Tauris; 2006) 268 pages. Social, political and cultural history of religious minorities in Iran, c. 226-1722 AD.

External links

- Religion Statistics from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Religion at the Open Directory Project

- Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents by Adherents.com August 2005

- IACSR - International Association for the Cognitive Science of Religion

- Studying Religion - Introduction to the methods and scholars of the academic study of religion

- A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right - Marx's original reference to religion as the opium of the people.

- The Complexity of Religion and the Definition of “Religion” in International Law Harvard Human Rights Journal article from the President and Fellows of Harvard College(2003)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||